The Crew’s Allotment

September 7, 1878

The Squall

September 11, 1878The true story of the HMS Challenger and one of the most important expeditions in history.

This article contains a republished excerpt from the Discovery article on the HMS Challenger.

The Challenger expedition was inspired, in part, by that age-old motivation: to prove somebody wrong. In 1843, a naturalist named Edward Forbes posited that “the number of species and individuals diminishes as we descend, pointing to a zero in the distribution of animal life as yet unvisited” at depths below 1,800 feet.

But several small expeditions hinted that he couldn’t be right: HMS Lightning and (the incredibly named) HMS Porcupine found animals like clams, scallops, and corals at depths below Forbes’ theoretical limit. In light of these discoveries (and perhaps spurred by telegraph companies’ desire to create more undersea cables), the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge approved a new, more thorough expedition: a three-year trip around the globe to plumb the ocean’s deepest basins, to ascertain the sea floor’s physical and chemical characteristics and to figure out just how far into the ocean’s depths life blooms.

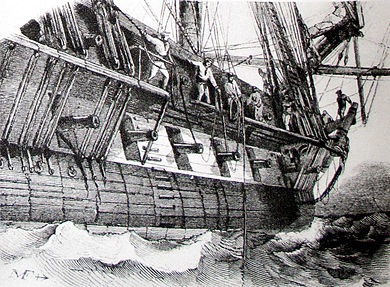

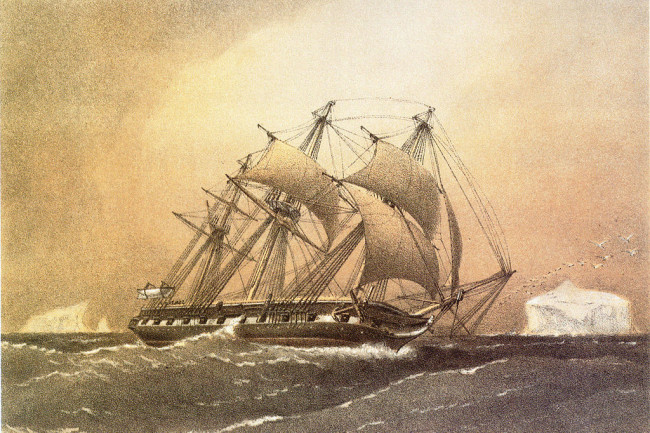

Challenger set sail four days before Christmas in 1872 out of Portsmouth on the southern coast of England. There were about 250 men on board, including six scientists, who the naval officers and crew nicknamed “the Scientifics.” Challenger was a small warship retrofitted for a scientific mission; 15 of her 17 guns were removed to make room for laboratories and equipment.

Before they set sail, the ship’s steward’s assistant, a 19-year-old named Joe Matkin, wrote to his cousin, “All the Scientific Chaps are on board, and have been busy during the week stowing their gear away. There are some thousands of small air tight bottles, and little boxes about the size of Valentine boxes packed in iron tanks for keeping specimens in, insects, butterflies, mosses, plants, etc. There is a photographic room on the main deck, also a dissecting room for carving up bears, whales, etc.”

The ship also carried 181 miles of Italian hemp rope that would be used to measure the water’s depth and lower dredges to the sea floor.

Every few days, Challenger sounded, or plunged a weighted line into the water to determine how deep it was. They also recorded the ocean’s temperature at various depths and dragged a weighted net with a 10-foot-wide mouth across a patch of the ocean floor and hauled aboard the sea creatures and sediments it dredged up.

Matkin wrote to his cousin, “When the dredge is hauled up [the scientists] stand round in their shirt sleeves, and commence overhauling the mud for fish etc., and as soon as they get any, down they all go to dissect and pickle them in glass jars.”

The crew sometimes brought in impressive specimens — one drawing from the expedition shows the crew hauling aboard a large shark, while two of the ship’s dogs watch warily.

Other times, though, the hauls were less exciting. “The mud! Ye gods, imagine a cart full of whitish mud, filled with minutest shells, poured all wet and sticky and slimy on to some clean planks,” wrote Sublieutenant Lord George Campbell about the sediments dredged from the sea floor. “In this the naturalists paddle and wade about, putting spadefuls in successively finer and finer sieves, till nothing remains but the minute shells.”

Halfway through the journey, in the spring of 1875, Challenger made one of its greatest discoveries: the Mariana Trench, containing the deepest point on Earth. The Mariana Trench is located near Guam, about 1,500 miles east of the Philippines. There, one of the Earth’s tectonic plates slips under another, resulting in a 1,580-mile-long groove in the seafloor.

At the lowest point Challenger recorded, the sea floor lay more than five miles below the water’s surface (later researchers would find that an even deeper point exists nearby, nearly seven miles deep). The crew wasn’t expecting the spot to be so deep; the first time they sent down a weight to measure the depth, they ran out of rope. When they sent down a thermometer, the glass cracked.

Captains Note:

The time period of Thousand Fathoms coincides with the desire to continue to discover and chronologe the sea and try to understand as much as we could. This same thought process can be found in novels by Jules Vern such as 20,000 leagues under the sea.